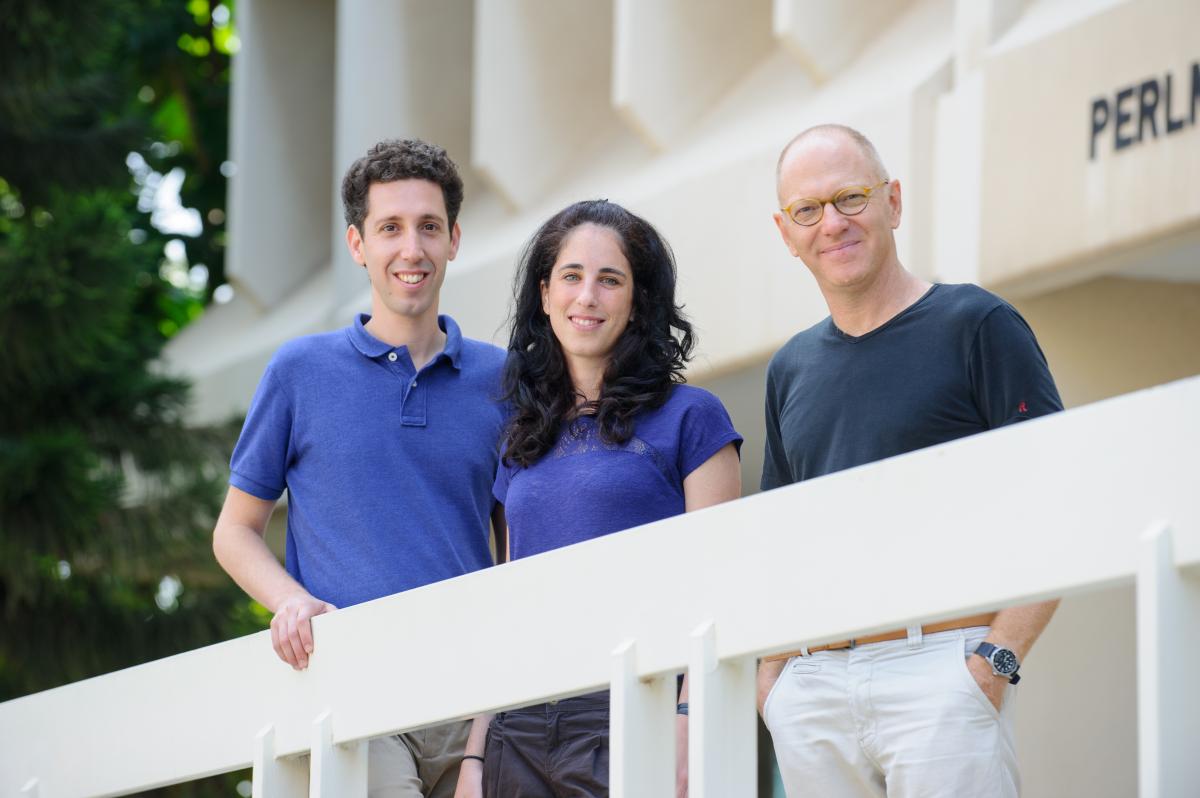

(l-r) Eyal Karzbrun, Alexandra Tayar, and Prof. Roy Bar-Ziv.

Cell-like compartments produce proteins and communicate with one another, similar to natural biological systems

Imitation, they say, is the sincerest form of flattery, but mimicking the intricate networks and dynamic interactions that are inherent to living cells is difficult to achieve outside the cell. Now, as published in Science, Weizmann Institute of Science researchers have created an artificial, network-like cell system that is capable of reproducing the dynamic behavior of protein synthesis. This achievement is not only likely to help us gain a deeper understanding of basic biological processes, but it may, in the future, pave the way toward controlling the synthesis of both naturally occurring and synthetic proteins for a host of uses.

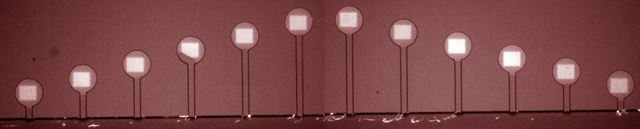

The system, designed by PhD students Eyal Karzbrun and Alexandra Tayar in the lab of Prof. Roy Bar-Ziv of the Institute’s Department of Materials and Interfaces, in collaboration with Prof. Vincent Noireaux of the University of Minnesota, comprises multiple compartments “etched’’ onto a biochip. These compartments – artificial cells, each a mere millionth of a meter in depth – are connected via thin capillary tubes, creating a network that allows the diffusion of biological substances throughout the system. Within each compartment, the researchers insert a cell genome – strands of DNA designed and controlled by the scientists themselves. In order to translate the genes into proteins, the scientists relinquished control to the bacterium E. coli: Filling the compartments with E. coli cell extract – a solution containing the entire bacterial protein-translating machinery, minus its DNA code – the scientists were able to sit back and observe the protein synthesis dynamics that emerged.

By coding two regulatory genes into the sequence, the scientists created a protein synthesis rate that was periodic, spontaneously switching from periods of being “on” to “off.” The amount of time each period lasted was determined by the geometry of the compartments. Such periodic behavior – a primitive version of cell cycle events – emerged in the system because the synthesized proteins could diffuse out of the compartment through the capillaries, mimicking natural protein turnover behavior in living cells. At the same time fresh nutrients were continuously replenished, diffusing into the compartment and enabling the protein synthesis reaction to continue indefinitely. “The artificial cell system, in which we can control the genetic content and protein dilution times, allows us to study the relation between gene network design and the emerging protein dynamics. This is quite difficult to do in a living system,” says Karzbrun. “The two-gene pattern we designed is a simple example of a cell network, but after proving the concept, we can now move forward to more complicated gene networks. One goal is to eventually design DNA content similar to a real genome that can be placed in the compartments.”

Fluorescent image of DNA (white squares) patterned in circular compartments connected by capillary tubes to the cell-free extract flowing in the channel at bottom. Compartments are 100 micrometers in diameter.

The scientists then asked whether the artificial cells actually communicate and interact with one another like real cells. Indeed, they found that the synthesized proteins that diffused through the array of interconnected compartments were able to regulate genes and produce new proteins in compartments farther along the network. In fact, this system resembles the initial stages of morphogenesis – the biological process that governs the emergence of the body plan in embryonic development. “We observed that when we place a gene in a compartment at the edge of the array, it creates a diminishing protein concentration gradient; other compartments within the array can sense and respond to this gradient – similar to how morphogen concentration gradients diffuse through the cells and tissues of an embryo during early development. We are now working to expand the system and to introduce gene networks that will mimic pattern formation, such as the striped patterns that appear during fly embryogenesis,” explains Tayar.

With the artificial cell system, according to Prof. Bar-Ziv, one can, in principle, encode anything: “Genes are like Lego, in which you can mix and match various components to produce different outcomes; you can take a regulatory element from E. coli that naturally controls gene X, and produce a known protein; or you can take the same regulatory element but connect it to gene Y instead to get different functions that do not naturally occur in nature.” This research may, in the future, help advance the synthesis of such things as fuel, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and the production of enzymes for industrial use, to name a few.

Prof. Roy Bar-Ziv’s research is supported by the Yeda-Sela Center for Basic Research.